When I first started coding, turning back some ten years ago, my main concern was to see my code working, by that time the understanding of working that I had, means the result be the expected one or in other words: answer what should be done. However day by day, that concerned has changed. I’ve added a second question to my development life-cycle: How development should be done, structured.

Object calisthenics show us, in an objective way, translated in nine programming best practices rules, a guide that we can follow to keep our code clean.

By best practices we can understand as a description of a standard way of doing things, in our context, coding, however not necessary means, the only way of doing that. Though in most cases this alternative approach can be considered code smell.

By clean code we can have different definitions, having some differences from one author to another, for this article I’ll assume code clean as a code:

- Easy to understand;

- Easy to modify;

- Easy to test;

- Works correctly.

Definition

Object Calisthenics are programming exercises, invented by Jeff Bay in his book The ThoughtWorks Anthology. The term Object is related to Object Oriented Programming and Calisthenics derived from Greek, meaning exercises under the context of gymnastics.

Although the term was first used in a Java development context, these rules are not dependent on any specific technology and yes, of course, as the name makes clear, dependent on an object oriented architecture.

Rules

- Only One Level Of Indentation Per Method

- Don’t Use The ELSE Keyword

- Wrap All Primitives And Strings

- One Dot Per Line

- Don’t Abbreviate

- Keep All Entities Small

- No Classes With More Than Two Instance Variables

- First Class Collections

- No Getters/Setters/Properties

Only One Level Of Indentation Per Method

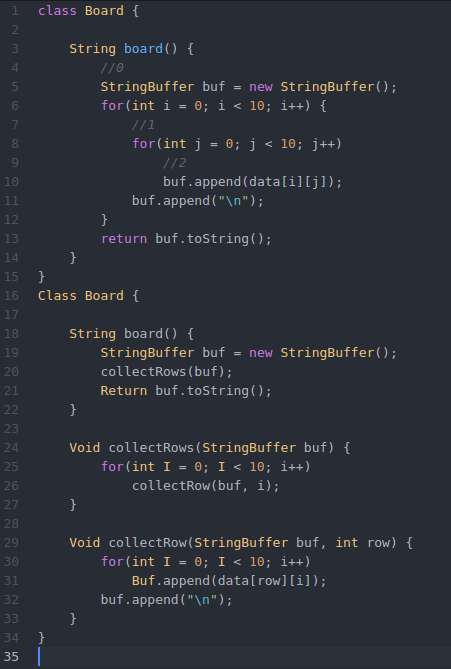

We start our exercise looking at the number of indentations in our code, this rule is extremely related with Extract method design pattern, actually their goals are the same.

We won’t reduce the line code’s number, but we will first increase readability and testability and second reduce the complexity of our methods in a significant way:

Don’t Use The ELSE Keyword

Every programmer understand the importance of the if-else-conditional structure and their simplicity. But the main ideal of this rule is to avoid complex conditional structures. Nearly every programmer has seen a nasty nested conditional that’s impossible to follow or a case statement that goes on for pages. Even worse, it is all too easy to simply add another branch to an existing conditional rather than factoring to a better solution.

In the image above we have three distinct solutions. The first clearly shows a code smell and also runs against the open-closed principle.

The second uses the early return approach which is the best option for the simplest structures, though is not considered a best practice in a pure object-oriented world for some authors and still runs against the open-closed principle, is considerable less verbose, better readable, and faster.

The third solution, probably the best for the most cases, uses the strategy behavioral pattern, that makes use of polymorphism through the use of interfaces, attending to the open-closed principle and also attending to our purposed exercise.

Wrap All Primitives And Strings

As mentioned by Jeff Bay on The Thought Works Anthology:

“An int on its own is just a scalar with no meaning. When a method takes an int as a parameter, the method name needs to do all the work of expressing the intent. If the same method takes an hour as a parameter, it’s much easier to see what’s happening. Small objects like this can make programs more maintainable, since it isn’t possible to pass a year to a method that takes an hour parameter”

So the basic idea is: If your primitive type has a behaviors, you must encapsulate it or a primitive obsession code smell can appear on your code.

One Dot Per Line

The main ideal here is to achieve high cohesion, build your class, method or any algorithm with a well defined job and of course with a single responsability.

But when we talk about responsibility, sometimes can be hard to define what is inside one class and what goes to the other, specially when we have generic names like UserService or SystemService, so first try avoid those names.

It is the direct use of the Law of Demeter, saying only talk to your immediate friends, and don’t talk to strangers.

The idea is to avoid constructions like below:

** father.getChild().setAge(10); **

And than became:

** father.setChildAge(10); **

The above is a very simple case, but image a situation with a three, four or more levels like: ** a.getB().getC().getD().getE().doSomething() ** would be terrible to understand and to test this code.

This rule doesn’t apply to Fluent Interfaces and more generally to anything implementing the Method Chaining Pattern (e.g. a Query Builder).

Do not Abbreviate

We have two main reasons to abbreviate:

Are you typing the same word over and over again? If that’s the case, perhaps your method is used too heavily, and you are missing opportunities to remove duplication;

Are your method names getting long? This might be a sign of a misplaced responsibility or a missing class.

This exercise establishes method or class names with one or two words without abbreviations and without context duplication, for instance if your class is named Client, a method name getClient is a context duplication.

Keep All Entities Small

Classes up to 50 lines and packages with no more than 10 classes. Some will say why 50? or why 10 classes? The easiest answer is: It’s just a number, a number for we measure our achievement. You can just define another, some argue that up to 150 lines is a good number.

The main idea here is to keep entities small, because large classes usually do more than one thing, which makes them harder to understand and harder to reuse. This is also described as a code smell: large classes and long methods.

No Classes With More Than Two Instance Variables

The hardest and indigested one, create classes with no more than two instance variables is based on the idea that a class can have only two types: those that maintain the state of a single instance variable and those that coordinate two separate variables.

Specially for those that came from dynamically typed languages like me things became even worst, some authors argue that for those languages five is considerable an ideal number.

It all boils down to decomposing complex structures into smallest ones, so choose your number and be consistent.

First Class Collections

This rule is an extension of Wrap All Primitives And Strings, and the idea is the same, each collection gets wrapped in its own class than every behavior related to them, now have a home (e.g. filter methods, applying a rule to each element).

No Getters/Setters/Properties

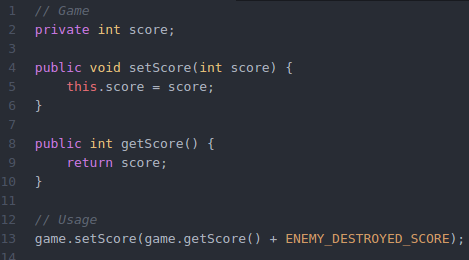

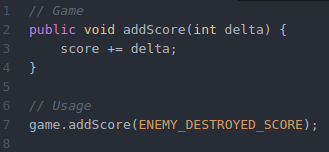

In a first sight, maybe looks weird, disallow a very common practice of creating getters and setters for almost all properties, however the basic idea here is avoid constructions like below:

Because we’re removing from the class their responsibility. The idea behind strong encapsulation boundaries is to force programmers working on the code after you leave it to look for and place behavior into a single place in the object model. The code above should look like above:

Conclusion

In conclusion these rules are all about writing maintainable code, they are an important and precise tool in which you can increase your software code quality. At first probably will be a great challenge but at the end the result will be awesome.